Museo della vita contadina "Cjase Cocèl"

Via Lisignana 22

33034 Fagagna

- Udine-

Tel. +390432/801887

cjasecocel@gmail.com

Vuoi rimanere sempre aggiornato? Lasciaci la tua mail:

MUSEUM OF AGRICULTURAL LIFE

Cjase Cocel is a farmers' house, similar to one of 50 years ago. Such houses, usually characterized by poverty and hard work, were the places in which men and women played out their entire existence before the advent of mechanized farming. Today’s visitors will find a wide display of tools used in agricultural work, as well as an itinerary which offers the opportunity to keep alive an interest in discovering one’s personal origins.

The museum

Cjase Cocel is an "eco museum" (from Greek oikos, which means house, birth place): it is an institution which aims to study, preserve, promote and display the memory of an entire community. Indeed, during the long period of the museum's installation, along with the restoration and cataloguing of objects, much attention was paid to historical memory through recollections and experiences of older people and those who lived in that period.

The house displays every-day Friulan life and typical Friulan agricultural work, and spans the period from the end of the Nineteenth century until 1950, before radical changes in life and work, occurred during in Friuli in the 1960s.

The building which hosts the Museum is an ancient rural building, dating back in some parts to 1600.

It has been purchased by the local council and renovated, maintaining the original characteristics which were typical of the Friulan farmhouse.

The name, Cjase Cocel, refers to the Chiarvesio family ( nicknamed Cocel), which lived in the house for many years. The family name has been maintained in order to evoke a local farming family and to emphasize the spirit of the institution of the museum, which recreates the house as it used to be in the past.

The visitor, indeed, has the impression of being in a lively place, an inhabited house, in which time has stopped. This is possible thanks to the presence of the people who carry out several traditional occupations, using old-fashioned tools. The visitor will encounter the knife grinder (gue), the basket maker (zeâr), the smith (fari), the spinner (filandere) and the lace maker.

Particular care has been taken in the creation of the broili, a small paddock to the side of the house, in which mulberry trees (necessary for the breeding of the silkworm), four rows of Friulan vines and a multiplicity of vegetables have been planted. Buildings hosting the activities of traditional occupations, such as the thresh, (trebie), the mill (mulin) and the smithy (farie) complete the reconstruction of the typical Friulan house.

The building

Analysis of existing maps confirms the existence of the housing complex from the 1700s.

The oldest part faces Riolo street. Indeed, the date "1687" is carved on the keystone of the arch, above the front door.

During the past three centuries, new buildings (both housing and agricultural), have been added to the original one in accordance with the growth of families and the development of agricultural activity.

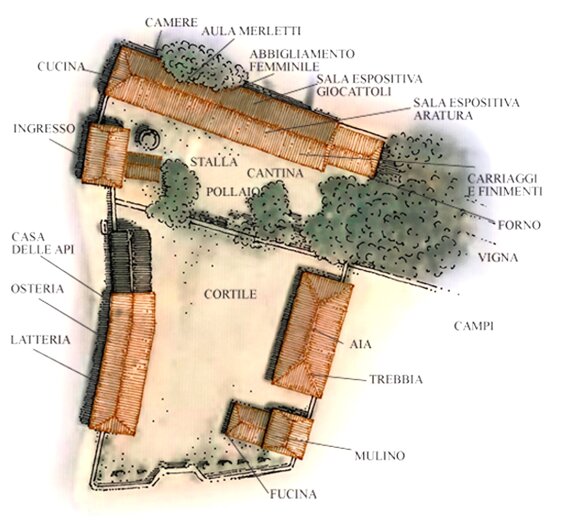

Suggested itinerary

The suggested itinerary ensures a full and “rational” visit to the Museum.

Following the list below, it is possible to visit the spaces dedicated to the old house and then the exhibition rooms.

1. Kitchen, fireplace, larder

2. Bedroom(stairs beside the kitchen)

3. Tool room (from here, you return downstairs)

4. Stable

5. Cellar

6. Farmyard

7. Granary

8. Exhibition room dedicated to ploughing

9. Exhibition room dedicated to clothing and textile fibers

10. Room dedicated to lace (return downstairs via the stairs to bedrooms)

11. Courtyard with well, mulberry tree, chicken coop, laundry room, bread oven

12. Vineyard (beyond the iron gate)

13. Thresh, wine press, cart (under the big canopy)

14. Mill

15. Smithy

First floor and ground floor

1. Entrance

2. Ticket office

3. Library

4. Toilets

5. Parking

Itinerary of the museum

1. The kitchen

The kitchen was the centre of domestic life of the Friulan family, and the most important area of the house. The word “cjase” or “house” has a particular significance in Friulan.

The kitchen was named “cjase di fur” to indicate its position away from the fireplace, the warmest part of the house.

The “cjase di fur” was not very warm as the heat of the fireplace did not reach it. Heat remained in the room which contained the fireplace, making it the ideal greenhouse for plants in winter time.

The kitchen of the museum has a square-like shape, walls whitened in a rural style, as the plaster has been applied directly to the stones, without skimming.

The ceiling consists of a beam of chestnut wood which supports planks of fir wood. The materials have been recovered from houses of the last century. Like the original kitchen, the floor has been realized with small rounded pebbles.

1.1 Le panarie (kitchen furniture)

The madia was the piece of furniture which conserved the flour in its upper part, closed by a flap.

Pirona defines it as follows: “the madia, a piece of kitchen furniture, consists of a chest covered by a flap and supported by four feet and two trestles. It is used to make bread dough; additionally, today it is used to contain the corn flour neededto produce polenta. Often the madia (panarie) was not sustained by trestles but incorporated into an underlining cupboard.

Dishes, bowls, crockery were found in the plate rail above the madia.

Usually on the plate rack the best plates and dishes were displayed. There was also dedicated space for cutlery.

1.2 Le vetrine (glass cabinet)

The glass cabinet consisted of two parts, the lower one, closed by two doors, was used to contain the crockery and pots; while the upper one, closed by two glass doors, was used to contain glasses and valuable objects positioned on shelves covered with crocheted lace.

The cups, instead, were hung by their handles on hooks.

Quite often photographs of relatives were inserted into the glass .

1.3 Le iluminazion (lighting)

Before the invention of electricity, the kitchen was lit by the “lampion” or oil lamp which hung on a hook from the ceiling. The “lum”, instead, was a small portable lamp equipped with a wick (el paver) and was moved from room to room.

1.4 El seglâr

Another characteristic element of the Friulan kitchen found in the “cjase di fur” was the sink.

The kitchen sink was made of stone, obtained from a single block and was supported by two pedestals made of stonework or brick.

Above it there was a wooden shelf with some hooks (picjots di fier) from which hung copper pails (cjaldîrs) for water usually taken from the well of the house or of the village. The pails were polished during festivities with a mixture of flour, salt and vinegar.

Laying on the side of the kitchen sink furthest from the wall was a wooden draining board (el-disgoteplats).

On the wall on the opposite side there was a rack with rounded tips to drain glasses (el-disgotetaces).

The sink was supplied with a hole for draining of water. Very often, at night, snails would enter the house from that hole, leaving a silver trail in their wake.

The only detergent used to clean the sink and the plates was a mixture of vinegar and flour.

On the shelf above the sink lids and bowls were placed as well as bowls with milk to make yogurt (caglade).

The kitchen sink of the museum is made of stone taken from a single block that is sustained by two brick supports. It has a wooden plate-rack on the left side, on the opposite side a “glass-rack” hangs from the wall.

Above the sink there is a wooden shelf supplied with iron hooks (picjots) from which copper pails were hung. Under the sink smaller pots were hung.

2. El fogolâr

Fundamental and characteristic element of the Friulan kitchen is the “fogolar” (fireplace), although it is believed that this amenity is a relatively recent custom.

Formerly in the Friulan houses the fireplace consisted of just four wooden planks positioned on the floor in the middle of the room.

A small window on the ceiling or, in warmer weather, the front door were openings for the smoke as there was no flue due to the fact that the ceiling was made of straw and the risk of fire was high. The absence of the flue caused the smoke to spread in the kitchen leaving soot on the wall and on the beam. This is the reason why the kitchen is called “cjase de fum” (house of smoke). People were used to the smoke and they just knew that if they sat , the smoke would remain above their heads.

The fireplace did not have a fixed position, being placed according to the layout of the house. The area dedicated to the fireplace was connected to the kitchen through an arch often closed by a glass door.

As the fireplace was the warmest part of the house, women, old people and children would eat around it together at lunch time.

A long bench running along three sides of the fireplace (bancjon) was used by guests and the family at mealtime.

Due to the fact that the fireplace was the warmest part of the house, some families used to lay young silkworms there to ensure their survival in cold weather.

The fireplace was positioned 50-60 cm above the floor, it had an external covering of brick and the mantelpiece was made of stone.

On the sides of the entrade, (a small arched opening), there were two flaps containing two burners used to cook food.

Above the base of the fireplace the cjavedâl, or andirons, were found. The cjavedâl was considered to be an object of value by the family as it was usually carefully crafted in iron and decorated by the blacksmith.

In some houses a specific hood, "le nape", was built especially when the fogolâr was not secluded. Sometimes, people would hang the just slaughtered pork around the hood. It was a tradition, on the first day of Lent, to hang a herring on the hood in order for it to be smoked. All members of the family, in turn, would have touched the fish with their ration of polenta, so they could taste... the "flavour". In some families, the householder would take the herring, touch it with his polenta and then thrown it to his oldest child who after taking his portion, would do the same thing with their next sibling and so on to the youngest of the family. A comic game, probably played to mask the lack of food. Then the herring was put away for the next day. A common trick of many housewives was to hang little canvas bags full of seeds of radicchio and salad on the hood, so that they could grow faster with the heat generated by the smoke of the chimney. The hood of the chimney, in the cold and dark winter evenings, was a mysterious and scary presence for the children. Saint Lucy, the Saint responsible of bringing presents to children, was very often represented as an old, blind woman, who would have punished whoever was awake at night; thus the dark hood of the chimney symbolised for many people her way into the house. The fireplace of the museum is found in a small room built on the west side of the kitchen. Another tradition in which the fogolar played an important role was Christmas. On Christmas day, the family would unite around the fireplace and burn for the entire night a big log "el nadalin". The log was then conserved for the year after. It was habit to pierce the log to let it burn more slowly and to create effects with the fire. In the past, the fireplace was only used to cook food and not for heating, as the family would retire to the stable after dinner.

3. El camarin (the larder)

Next to the kitchen the larder (el camerin or stanzein) was found, usually hidden under the stairs. The floor was earthen and there was a small window on the north-east wall to keep the room cool. The key of the room was jealously guarded by the mistress of the house, as the larder was a precious room used to conserve the treasures of the family. When the mother-in-law was absent, the key was kept by

the oldest sister-in-law. In the larder, which was usually long and narrow, the supplies of the family were conserved. The salami hung from the stangjes, a series of parallel sticks at 30-40 cm from the ceiling; the rounds of cheese, le pieces, were put on a suspended board. On the wires holding the board people used to put small packets of holly to keep away the mice. The cheese and the salami already opened (disniçats) were kept in the moscjarole, a cage-like structure with a very thin net to avoid contamination by flies and mice. In the larder were also found terracotta vases used to conserve the pork fat (gras or sain) the only condiment used. In those vases eggs were conserved in a solution of water and lime, that blocked the pores to make them last longer. In the camarin a small supply of wine was also stored.

4. Workshop

In winter, when there was less work on the farmland, the farmer dedicated time and care to the upkeep of the house and the agricultural equipment.

The workshop (stanzie dai imprescj) was his work space, where he carried out simple restoration work and where he kept the equipment used on the farmland (pruning hook, sickle), in the vineyard (bellows for treating vines with sulphur) and in the courtyard (funnel to feed geese with).

In the museum workshop, there are other traditional tools of the stanzie dai imprescj: the vise (smuarse), the saw (see) and the plane (splane) used to manufacture or repair the wooden handles of tools, as well as clogs and kitchenware. A grindstone (muele) used to sharpen blades is also exhibited. These tools belonged to three professions, that worked in the agricultural community of the past: the carpenter (marangon), the “norcino” or pork butcher (purcitâr), the cobbler (cjaliâr), which are showcased here.

The "norcino" (the person responsible for butchering pigs) was equipped with many tools such as knives, funnels, a mincer and his own jar of herbs and spices (mindusies). Inside the family’s home, he would have found the taulaç, a large table, the pestadorie, a wooden tub supported by three feet with a concave interior used for breaking the pork rind with a peston and the cjalderie, a big copper pot for boiling water and melting the fa..

The shoemaker often worked in tiny workshops filled with wood, casts, hides, a shoemaker’s bench complete with tiny tools and a machine for sewing the uppers. A part of his work was dedicated to the production and repair of leather harnesses (comat, tiredôrs, reghines).

5. The stable

An essential part of the Friulan farm was the stable (stale) which was not only a shelter for domestic animals (cows, oxen, steers and calves ) but also a meeting point for the families of the local area on winter nights. This modest space was usually built next to the kitchen (cjase), often with an interconnecting door to allow the passage of heat. It generally hosted a pair of cows providing milk and a couple more providing meat. Room for the calves was carved out behind a small, wooden partition.

The animals were tied to a manger (grepie) which was placed along the main wall, with its back to the entrance door. Thanks to this position, the animal manure was easily removed and the new bedding for animals (scjerni) was changed daily.

Above the stall was the hay- loft, which was connected by a trap-door (trombe), from which hay was dropped. There were few tools: some chains, the muzzle (cos), the stool used for sitting while milking, a small wooden trough for bran and other supplements (concje), wooden collars for the calves.

From a social point of view the stall had great importance and hosted the evening meeting (file), during which women span or sewed under the pale light of an oil lamp; men fixed tools, while talking to each other; and children slept or listened to the stories which were narrated by adults. The "file" (the evening meeting) usually continued until the Easter period.

6. The wine cellar

The wine cellar of the museum is fitted out with artifacts coming from old, dismantled cellars.

Here we find all the tools necessary for winemaking. The vat (brancjel), the big barrel (bote) and the small one (caratel) are noteworthy. In these containers we can note the cjalcon, which is a wooden cork that seals the hole at the bottom of the barrels from which the wine comes out.

There are also wooden containers, which are used in the cellar (brente) and wooden tubs (sentine) which were placed to collect the wine either under the vat (rounded ones) or under the press (oval ones). Other tall and narrow containers were needed for measurements. Above the barrels there are several wooden funnels (plere) with different shapes and sizes made to balance on the convex tops of the barrels. Inside the barrels the white wine was boiled, immediately after being separated from the marc. In order to check the temperature and to allow gas to escape, the bolidôr, an iron tube, the shape of a hook, was used.

One side of the funnel was inserted and sealed in the upper hole of the barrel, while the other passed through a small bowl full of boiling water and wine which was needed to regulate the time of fermentation.

The red wines (black) fermented in open vats, almost filled up to the rim.

This boiling caused the marc to rise (el vin al dave sù la trape); a wooden tool with spokes was used to turn the marc over, in this way the grape must at the bottom would gain a proper colour and strength. Fermentation time varied depending on the type of grapes used (3-5 days). The first phases of fermentation usually took place in wine cellars which did not belong to the winemaker, the foladôrs and the turclis were usually borrowed or else the grapes were carried to the farmhouse wine cellar). To transport the barrels, a wooden tool (scjalon) was used to load and unload them onto the wagon by rolling them over a wooden track. In the museum’s wine cellar, we can find the "machines" usually employed in winemaking: the stalk-removing machine (machine masane ue o machine par folâ) and the winepress (turcli). The stalk-removing machine had replaced the traditional grape trading (folâ), which was used in the past by all the farmers. The de-stemming machine was owned by the major landowners and usually moved from one wine cellar to another, it completed the work of the ordinary press (exhibited above the vat); it is a noteworthy example of a mobile model. Its usage is quite simple: the mechanical movement sets two rollers in motion, these grind the grape brunches, and a toothed bar, which eliminates the grape stalk which was of no use in the winemaking process: the must (most) and the skin (cufui) are collected in the underlying wooden tank. The pressing machine completes the process by squeezing the marc in order to obtain the second wine, which passes through a sieve before going into the oval wooden tub.

7. The arie

In the agricultural house, the arie is the closed space in which the wagons and other rural tools are kept.

This area, characterized by a wide opening onto the courtyard, which was often closed by a wooden door, was used as a temporary store place for the crops (e.g. corn on the cob).

7.1 The carete

The cart (carete) was used to transport people and, if necessary, after the seats (le sente) had been removed, could be used to transport small quantities of agricultural products.

In order to enhance the family’s prestige, great care was given to the "architectural" and the constructive elements. As the vehicle was pulled by horses or donkeys, not every family could afford it.

7.2 The briscje

Like the carete, this vehicle was an indication of the wealth of a family..

The briscje had similar functions to those of today's van, indeed it was employed in the transport of both people and loads. Its origin is shown by the names briscje, a typical Slavic name, and guriziane, which suggests the area in Friuli from which it spread.

7.3 El cjar (the wagon)

The agricultural wagon is, in several ways, a symbol of Friulan modernization: like the plough it was essential for agricultural work, and it showcased the great technical knowledge of the cartmakers (carîers).

It had many uses: it was used as a means of transport for hayloads or cereal stacks; after removal of the stepladders, it was suitable for the transport of agricultural tools; if the sides were lifted, it was possible to transport potato and corn on the cob harvests. In addition, by using vertical poles (stedeis), fixed into the "partite" in place of the loading bed, it was used for the transport of timber and baskets.

8. The tools

8.1 The cart

Connected with the use of the cart are the following tools:

Tulugn: a winch in the posterior part of the cart, that is turned by winding a rope attached to the end of the jubâl.

Jubâl: a long wooden pole used to box in the load of hay.

Predêl: a pole used as an extension of the helm of the cart to hitch more oxen.

Binte: a lever, used to raise the cart and turn the load out.

Leverin:a lever, used to raise the cart to repair it or to change a wheel.

8.2 The harne

Jôf: a yoke, a wooden crossbeam with two openings, adapted to fit the neck of the oxen and buckled onto the end of the helm or of the predêl with a double twist. (cerce or tuarte).

Jovet: a collar, similar to the above yoke but adapted for just one ox, hitched in front of other coupled oxen.

Comat e comatele: a collar for horses, formed by two little wooden arches united to form an acute angle at the top and a large curve on the opposite side. It’s covered with leather and filled with straw or horsehair. The comatele was put on the neck of the horse under the comat as a protection.

Reghines: bridles, leather strips attached to the bit of the horse to control and guide it.

Smuars: the iron part of the bridles put in the mouth of the horse to control and stop it. Its parts are:

- Canon: the mouthpiece

- Strangjetes: the two shafts at the endings of the mouthpiece.

- Voi, ocjetons, barbonsâl, rampin.

Cjavece: halter, leather or rope harness. It was put over the head of equines and bovines to walk them by hand or to fasten them to the manger.

Argagn: harness to hitch an ox, a cow or a donkey before other oxen.

8.3 For the haymaking

For haymaking, hay conservation and work in the shed, the following tools were used:

“Falcet”: scythe characterized by 2 handles made of wood (falciàr), a blade made of steel and wooden wedges called “coni” which secured the blade to the handle.

“Batadorie”: tiny anvil on which the edge of the hay scythe, deformed when hitting stone, was straightened with the use of a hammer. The anvil, the hammer and a small chain together are called “batadories”

“Codàr”: horn, container obtained from a piece of wood and a bovine horn that agricultural workers hung on their belt behind their back. In contains water and a sharpening stone to whet she scythe. This stone is called “cote”; in Friulan “còt” means: stone or rock.

“Riscjele”: rake made of wood used to collect hay in the steepest places (rivàls) and then to level off the hay on the waggon (petenà el cjar).

“Riscjelon”: rake with a wooden handle and iron prongs used in flat areas. In enables quicker work. Pulled by a horse its use was widespread in the ‘50s: two wide strips of hay could be collected (tirà donje).

“Forcjes di len”: hayfork with 2 or 3 prongs for transporting hay into the hayloft.

“Lincin”: cane provided with an iron hook used to take hay from the top of the heap and transfer it to the hayloft.

“Tace fen” or “tacon”: hay cutter; needed to cut the heap (tasse) vertically.

8.4 For the harvest

For harvesting, conserving, refining and using cereals the following tools were used:

“Pietin pal soleàr”: similar to a large comb with wide teeth made of wood. It wasused to comb rye hay (soleàr). It was placed on trestles.

“Batali”: tool used to beat hay or rye. It is composed of a long handle, a kind of cudgel and a strip of leather binding them.

“Plee forment”: type of rake equipped with a curved handle. It was used in the mowing process with a machine pulled by horsed in order to collect cut wheat and form “mannelli”.

“Tace manjadure”: tool used to cut corn plants with leaves (without cobs) that became food for bovines (manjadure).

8.5 In the fields or in the farmyard

Other tools were employed in fields or in the farmyard:

“Grape”: harrow constructed of 3 parallel wood beams of a bout 2 meters long (paranjes) assembled together by three other wood beams from which long iron prongs stick out.

“Segnadòr”: big rounded basket made of wicker of really wide weaves. It was used to transport animals and small quantities of products on the waggon. Turned upside down in was employed in the yard in order to protect the mother hen and her chicks from attacks by rapacious birds. Sometimes it was used as a box for children while the mother was involved in working outside.

“Cos”: big rectangular basket made of wicker. It could have many dimensions and capacities. 2 or 3 “cos” were placed on the waggon to transport cobs, terrain and fertilizer

8.6 The old house

8.6.1 Le cjamare e il jet (the bedroom and the bed)

The furniture in the bedroom was essential: the bed (jet) could be double or –like the one exhibited in the museum- a bit larger than a single one (di une persione e mieze). The tallboy (l’armàr), the bedside tables (I laterài), the cradle made of wood or wicker (scune alte) , the chest for the dowry (casse), the washbasin (lavandin). The bed is made with linen sheets, woven and embroidered by hand with big red cross-stitched initials (L.P.).

The cotton bed cover was made of white crochetwork. Above the bedhead (concjete) a huge painting of the Sacred Family and a holy water font (el bussui de aghe santé) are hung.

“El lavandin”: the washbasin.

In the bedroom, generally, there was room for the washbasin. It is possible to find different types: tables on which to place basin and jug, stands or consoles. This washbasin stand is equipped with a shelf for soap and even a mirror (not on display). In the bedrooms during winter the water in the basin froze because of the pungent cold and it was necessary to break the ice in order to wash. Towels were part of the bride’s dowry and were precious and embroidered depending on financial circumstances.

“bussui de aghe sante”: the holy water font.

It was hung on the wall. Before sleeping the bed was blessed with holy water and the sign of the cross was made.

“Le scune”: the cradle.

Babies were placed in baskets supported by wooden trestles (similar to beds). These was convenient because they could be transported to the kitchen, so that the baby could be supervised by the mother while she was working.

The “scune alte” is a wooden cradle with a slightly curved base which could be rocked.

The oldest type of bed was supported by trestles (jet sui cavalets). The cavalets (trestles) are low, made of wood and sometimes decorated.

Above the trestles, to form the real bed, wooden boards were placed. These supported the mattress (stramaç) which consisted of a big cloth sack, usually decorated with white and blue squares, filled with dried leaves of maize (scartos).

("When the cob leaves had been stripped off they were used to fill the straw mattress" )

The upper part of the sack was provided with four cuts to shake up the leaves, this was usually done every morning.

Those who could afford it had a quilt mattress above the scartos in winter. It was taken off in summer to stay cooler.

This type of bed was still in use among the poorest families of this area until the middle of the twentieth century,. Wealthier couples could avail of more comfortable beds (le cocjete) from 1920.

The cocjete is the frame or the structure of the bed (brees) with rails that support the mattress which contained leaves (paion) or springs (moleton - elastic). This term was used to indicate the frame of the bed made of iron but especially of wood.

The cocjete is the most important piece of furniture for the married couple.

The parts of the cocjete are the cocjete da cjâf (bedhead), the da pît (footboard) and the bandineles (sides of the bed).

Beds were not very large because the rooms were very small and often an entire family slept in one room.

Museo della vita contadina "Cjase Cocèl"

Via Lisignana 22

33034 Fagagna

- Udine-

Tel. +390432/801887

cjasecocel@gmail.com

Vuoi rimanere sempre aggiornato? Lasciaci la tua mail: